Victoria Flle - Tumblr Posts

Der Sambesi ist mit über 2 700 Kilometer Länge die wichtigste Lebensader im südlichen Afrika. Er entspringt im Hochland von Sambia. Durch kleine Bäche und Nebenflüsse entwickelt sich der Fluss auf seiner 2 800 Kilometer langen Reise zu einem gewaltigen Strom.

In seinem Einzugsgebiet leben 40 Millionen Menschen. Sein Fischreichtum versorgt 60 Völker, sein Wasserweg verbindet sechs Länder. 1855 stieß der schottische Missionar und Abenteurer David Livingstone auf die Wasserfälle und benannte sie nach der damaligen britischen Königin Victoria.

The Zambezi is the most important lifeline in southern Africa with a length of over 2,700 kilometers. It originates in the highlands of Zambia. Through small streams and rivers, the river develops into a huge stream on its 2,800 km journey.

40 million people live in its catchment area. Its wealth of fish supplies 60 millions of peoples, its waterway connects six countries. In 1855 the Scottish missionary and adventurer David Livingstone came across the waterfalls and named them after the then British Queen Victoria.

Zimbabwe is a landlocked country in southern Africa known for its dramatic landscape and diverse wildlife, much of it within parks, reserves and safari areas. On the Zambezi River, Victoria Falls make a thundering 108m drop into narrow Batoka Gorge, where there’s white-water rafting and bungee-jumping. Downstream are Matusadona and Mana Pools national parks, home to hippos, rhinos and birdlife.

Simbabwe ist ein Binnenland im Süden von Afrika, das für seine beeindruckende Landschaft und vielfältige Fauna in Parks, Reservaten und Safarigebieten bekannt ist. Am Sambesi donnern die Victoriafälle über 108 m hinab in die schmale Batoka-Schlucht, wo Rafting und Bungee-Jumping angeboten werden. Flussabwärts liegen die Nationalparks Matusadona und Mana-Pools, wo Nilpferde, Nashörner und verschiedene Vogelarten leben.

The Victoria Falls Hotel breathes history: portraits of the historical figures from the founding period and famous guests adorn the walls of the corridors of the "Grand Old Lady of the Falls", as the hotel is affectionately called. Built in 1904, at the time of Edward VII, it offers all the amenities you would expect from a hotel of this category, combined with a unique location directly above the Victoria Falls.

Das Victoria Falls Hotel atmet Geschichte: Porträts der historischen Persönlichkeiten aus der Gründungszeit und berühmter Gäste schmücken die Wände der Korridore der "Grand Old Lady of the Falls", wie das Hotel liebevoll genannt wird. Es wurde 1904 zur Zeit von Edward VII. Erbaut und bietet alle Annehmlichkeiten, die man von einem Hotel dieser Kategorie erwarten würde, kombiniert mit einer einzigartigen Lage direkt über den Victoriafällen.

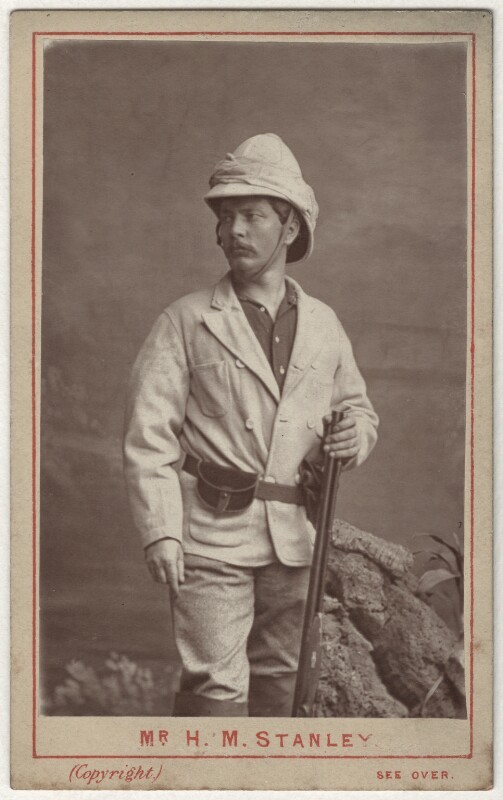

Stanley's Terrace at the famous venerable Victoria Falls Hotel:

And Stanley's Room at the famous venerable Victoria Falls Hotel:

November 10th 1871 saw the Journalist Henry M Stanley find the missing Scottish missionary David Livingstone with the classic “Dr Livingstone, I presume?”

David Livingstone arrived in Africa in 1840 with two goals: to explore the continent and to end the slave trade .Back home his writings and lectures ignited the public’s imagination and elevated Livingstone to the status of a national hero. In 1864 Livingstone returned to Africa and mounted an expedition through the central portion of the continent with the objective of discovering the source of the Nile River. As months stretched into years, little was heard from the explorer. Rumours spread that Livingstone was being held captive or was lost or dead. Newspapers headlined the question “Where is Livingstone?” while the public clamoured for information on the whereabouts of their national hero.

By 1871, the ruckus had crossed to the shores of America and inspired James Gordon Bennett Jr, himself a second generation Scots-American, and publisher of the New York Herald, to commission newspaper reporter Henry Stanley to find Livingstone.

Leading an expedition of approximately 200 men, Stanley headed into the interior from the eastern shore of Africa on March 21, 1871. After nearly eight months he found Livingstone in Ujiji, a small village on the shore of Lake Tanganyika on November 10, 1871.

There is nothing better than the first hand eye witness accounts of history and Stanley being an adept reporter meticulously wrote everything down, the following is his account on finding Livingstone.

“We push on rapidly. We halt at a little brook, then ascend the long slope of a naked ridge, the very last of the myriads we have crossed. We arrive at the summit, travel across, and arrive at its western rim, and Ujiji is below us, embowered in the palms, only five hundred yards from us! At this grand moment we do not think of the hundreds of miles we have marched, of the hundreds of hills that we have ascended and descended, of the many forests we have traversed, of the jungles and thickets that annoyed us, of the fervid salt plains that blistered our feet, of the hot suns that scorched us, nor the dangers and difficulties now happily surmounted. Our hearts and our feelings are with our eyes, as we peer into the palms and try to make out in which hut or house lives the white man with the grey beard we heard about on the Malagarazi.

We are now about three hundred yards from the village of Ujiji, and the crowds are dense about me. Suddenly I hear a voice on my right say, ‘Good morning, sir!’

Startled at hearing this greeting in the midst of such a crowd of black people, I turn sharply around in search of the man, and see him at my side, with the blackest of faces, but animated and joyous, - a man dressed in a long white shirt, with a turban of American sheeting around his woolly head, and I ask, 'Who the mischief are you?’

'I am Susi, the servant of Dr. Livingstone,’ said he, smiling, and showing a gleaming row of teeth.

'What! Is Doctor. Livingstone here?’ 'Yes, Sir.’ 'In this village?’

'Yes, Sir’

'Are you sure?’

'Sure, sure, Sir. Why, I leave him just now.’

In the meantime the head of the expedition had halted, and Selim said to me: 'I see the Doctor, Sir. Oh, what an old man! He has got a white beard.’ My heart beats fast, but I must not let my face betray my emotions, lest it shall detract from the dignity of a white man appearing under such extraordinary circumstances.

So I did that which I thought was most dignified. I pushed back the crowds, and, passing from the rear, walked down a living avenue of people until I came in front of the semicircle of Arabs, in the front of which stood the white man with the grey beard. As I advanced slowly toward him I noticed he was pale, looked wearied, had a grey beard, wore a bluish cap with a faded gold band round it, had on a red-sleeved waistcoat and a pair of grey tweed trousers. I would have run to him, only I was a coward in the presence of such a mob, - would have embraced him, only, he being an Englishman, I did not know how he would receive me; so I did what cowardice and false pride suggested was the best thing, - walked deliberately to him, took off my hat, and said,

'Dr. Livingstone, I presume?’

'Yes,’ said he, with a kind smile, lifting his cap slightly.

I replace my hat on my head and he puts on his cap, and we both grasp hands, and I then say aloud, 'I thank God, Doctor, I have been permitted to see you.’ He answered, 'I feel thankful that I am here to welcome you.’

Should you pick up on the "being an Englishman” words remember these were Stanley’s words, and he really should have known better, he himself was from Wales originally, leaving when he was just 15 to make his way to the USA.

Stanley joined Livingstone in exploring the region, finding that there was no connection between Lake Tanganyika and the Nile. On his return, he wrote a book about his experiences: How I Found Livingstone; travels, adventures, and discoveries in Central Africa.