15th Century - Tumblr Posts - Page 2

Virgin and Child, Andrea Mantegna, 1485-1491, Cleveland Museum of Art: Prints

Size: Sheet: 25.8 x 24 cm (10 3/16 x 9 7/16 in.) Medium: engraving

https://clevelandart.org/art/1956.741

the children of Richard Plantagenet and Cecily Neville, Duke and Duchess of York

♕ Daughters of James I of Scotland and Joan Beaufort (requested by anonymous)

sigynofasgard replied to your post: ID THIS LOSER

ooc: Googled it - maaaan what a load of - well “propaganda” is a nice term. :-p

I know, that is putting it kindly.

Though I’ve been doing some reading up on the concept of “Tudor Propaganda,” and have come across some pretty convincing stuff that argues that the notion that the Tydder’s admin promoted an active agenda of propaganda blackening Richard III’s legacy is largely false. This really surprised me!

But even more interesting is the point that this author made that Henry’s policy was basically “we don’t talk about that shit” and was more devoted to obscuring the known facts rather than actively manipulating them. Which was its own kind of propaganda, I guess. So a good example is the fact that when Henry’s first parliament repealed the Titulus Regius act of 1484, not only did they not read the act aloud, or even refer specifically to the contents of it, but every copy of it was ordered to be destroyed, or turned in to the authorities for destruction, on pain of serious fines or forfeiture.

A lot of other interesting stuff in the article as well, especially wrt the complete non-treatment of the missing sons of Edward IV during Henry’s reign. The ref: C. S. L. Davies, “Information, Disinformation, and political knowledge under Henry VII and early Henry VIII” Historical Research 85:228 (2012), 228-53.

It’s really pretty fascinating, and makes the point that the Polydore Vergil and Thomas More versions of the events of 1483-85 didn’t gain wide circulation until the 1530s and 1540s.

My mind was pretty blown. I may even have done the dramatic forehead slap a couple of times.

The White Princess episode 6 | Perkin Warbeck and Cathy Gordon ✥

“He was thirty-two years old, had reigned two years, one month, twenty-eight days. The only language, it turned out, in which he had been able to communicate himself successfully to the world was the terse idiom of courage, and the chief subject he had been given to express was violence. It had begun for him as a child in violence and it had ended in violence; the brief span between had been a tale of action and hard service with small joy and much affliction of spirit. If he had committed a grievous wrong, he had sought earnestly to do great good. And through his darkening days he had kept to the end a golden touch of magnanimity. Men did not forget how the last of the Plantagenets had died. Polydore Vergil, Henry Tudor’s official historian, felt compelled to record; “King Richard, alone, was killed fighting manfully in the thickest press of his enemies.””

— Paul Murray Kendall

Portrait of Catherine of Aragon, Juan de Flandes, ca. 1496.

Owen Tudor was born in Anglesey, Wales around 1400. Owen was born into one of the most powerful families in Wales, although like many, their influence had been greatly reduced by Edward I’s conquest and the family’s loyalty to Welsh independence. Owen was descended from Welsh kings on both sides of his family. During the Glyndwr rebellion of 1401, Owen’s father and uncles sided with Owain Glndwr as he was their maternal cousin. The Tudur brothers were loyal to the last, Owen’s uncle Rhys as executed in 1412 and their lands were confiscated by the crown, Owen’s father Maredudd disappears from record after 1405, but it would seem likely he did not live long after.

Not much is known about Owen’s early life, it has been suggested he may have been one of Welshman who served with Henry V at the battle of Agincourt, Owen was certainly in the service of the king by 1421. It is known that Owen served the young dowager queen, Catherine of Valois as her keeper of household or wardrobe. After her husband’s death Catherine lived at Leeds Castle, where she was more or less forgotten about and had no official role in her young son’s reign and was forbidden by parliament to marry again without their approval. Sometime between 1427 and 1430 Catherine and Owen fell in love and married secretly, their marriage was not made public until 1432 and was not received well, although Owen was granted the rights of an Englishman.

Owen and Catherine had 3 to 4 children, their sons, Edmund and Jasper, and it is likely they had at least one daughter Margaret who may have died young or became a nun, and a son Edward who also joined the clergy. The existence of Margaret and Edward remain inconclusive however. Catherine died in 1437, after her death Owen was left without protection and was imprisoned in Newgate which he would escaped from twice. Eventually Edmund and Jasper were received at court as their half-brother Henry VI who was very fond of them.

Owen supported Henry VI against Henry’s cousin the Duke of York, in what would become the 30- year conflict of the War of the Roses, Owen fought at the battle of Mortimer’s Cross in 1461, where he was captured and quickly and illegally put to death by Edward of York, the future Edward IV. However his grandson Henry Tudor would become the eventual victor at the Battle of Bosworth on August 22nd, 1485, making Owen the direct ancestor of every English monarch since.

A nice chicken I encountered in the margins of a Haggadah, the ‘Ashkenazi Haggadah,’ with commentaries attributed to Eleazar Ben Judah of Worms, c. 1430.

The British Library

10 Lavishly Illustrated Medieval Haggadah Pages That Continue to Reveal Their Secrets

“How does this book on Jewish manuscript illumination differ from all other such books?”

Marc Michael Epstein could not resist posing the question in “Skies of Parchment, Seas of Ink: Jewish Illuminated Manuscripts,”a sweeping, lavishly illustrated—and yes, illuminating—survey out this week from Princeton University Press.

Nine scholars join Epstein in this innovative anthology of essays chronicling the history of these manuscripts—the Bible, the Haggadah, the prayer book, marriage documents, and other Jewish texts—from the middle ages to the present.

The goal was to push beyond tradition and examine the manuscripts from a broader perspective, considering artistic style, iconography, narrative, cross-cultural borrowings and references.

One example is the enigmatic (so-called) Birds’ Head Haggadah, probably illuminated in Mainz around 1300—the earliest surviving example of the phenomenon of the obfuscation of the human face in such a manuscript.

What are these strange beaked creatures? Tracing the imagery back to the cherubs on the Ark and the curtain of the Holy of Holies, Epstein explains why volume would be more accurately known as the Griffins’ Head Haggadah.

In the spirit of the season, here are 10 Haggadah pages discussed in this fascinating new book.

1. “We were slaves to Pharaoh in Egypt.” The lower margin and central illustration depicts the slaving Israelites, while at top, a hare is served a drink by a dog, perhaps articulating the wish that “one day the Egyptian dogs will serve us.” The Barcelona Haggadah, Spain, ca. 1340. British Library, London.

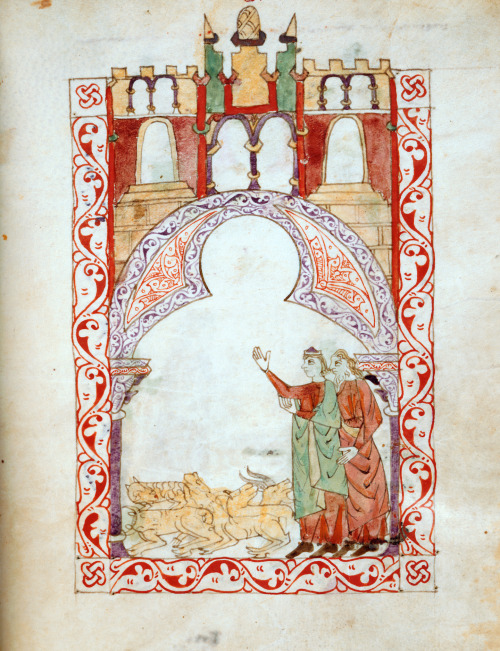

2. Moses and Aaron before Pharaoh, rendered in a“primitive” style in the Hispano-Moresque Haggadah from Castile, Spain, ca.1300. British Library, London.

3. The Wise Child in a Haggadah illuminated by Nathan ben Abraham Speyer of Breslau. Silesia, Germany (now Wrocław, Poland), 1768. National Library of Israel, Jerusalem.

4. Armed Israelites crossing the Red Sea in the Rylands Haggadah, Catalonia, Spain, mid and late 14th century. John Rylands University Library, Manchester.

5. Israelites crossing the Red Sea in a Haggadah written and illustrated by Joseph Bar David of Leipnick, Moravia. Darmstadt, Germany, 1733. Library of the Jewish Theological Seminary, New York.

6. The Ten Plagues in a Haggadah with the commentary of Abravanel, written and illustrated by Judah Pinḥas, Germany, 1747. Friedrich-Alexander Universistätsbibliothek, Erlangen-Nuremberg.

7. Maror, the bitter herbs (in the Brother Haggadah), Catalonia, Spain, third quarter of 14th century. British Library, London.

8. Disputing and frustrated figures populate a scene where women learn together and with men. First Darmstadt Haggadah. Middle Rhine, second quarter of the 15th century. Hessische Landes und Hochschulbibliothek, Darmstadt.

9. Israelites building store-cities for Pharaoh. Haggadah illustrated by Joseph Bar David of Leipnick, Moravia. Altona, Germany, 1740. British Library, London.

10. The Binding of Isaac in the manuscript traditionally known as the Birds’ Head Haggadah, Upper Rhine, Germany, ca. 1310. The Israel Museum, Jerusalem. Epstein argues that the volume should be called the Griffins’ Head Haggadah.

Richard, Duke of Gloucester, was the youngest son of Richard, Duke of York and Cecily Neville. By the time his brother became King Edward IV, when Richard was just eleven, he had already endured many hardships, including the deaths of his beloved father and eldest brother Edmund, and foreign exile. However, he soon proved himself to be a young man of character: he was a valiant warrior and a fiercely loyal subject. Though he (likely already) had two illegitimate children when he married Anne Neville, he seems to have been faithful to her—highly unusual for the time. Richard was, of course, hardly a saint. Yet while questions remain concerning his actions following Edward’s death in 1483, the fact remains that he was a remarkably successful and socially-conscious king despite his his brief reign. He died bravely in the summer of 1485 and remains the last English king to have fallen in battle.

Page of the Ashkenazi Haggadah, published in the 15th. Century in what would become modern day south Germany. This page contains the recitation “Ha Lachma Anya”, translated in full here: “This is the bread of affliction that our ancestors ate in the land of Egypt. Anyone who is hungry should come and eat, anyone who is in need should come and partake of the Pesach sacrifice. Now we are here, next year we will be in the land of Israel; this year we are slaves, next year we will be free people”.

Toreador lovers from my renaissance themed campaign. Not sure if it`s ok to tag that as vtm, as I tried to make them look less like vampires and more like regular humans. Youngest son of a Florentine nobleman and a famous painter from Siena, still clinging to mortal identities and beliefs. No need to be a monster yet, they have centuries to lose everything that is dear to them. Just a moment of inner peace and sensuality, years before everything goes wrong.