Nothing special, just history, drawings of historical figures in some… er… non-canonical relationships and fun! 🥂25 year old RussianHe/him

258 posts

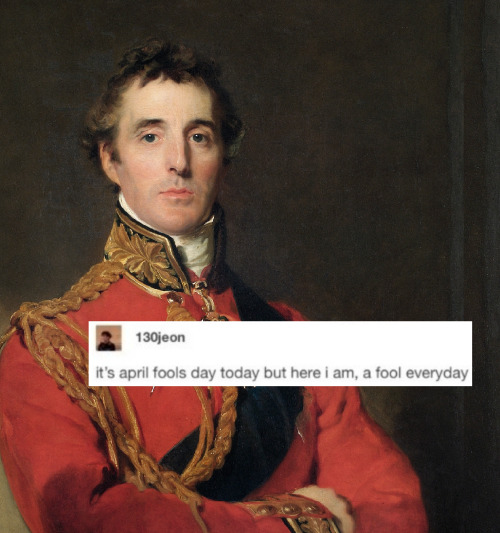

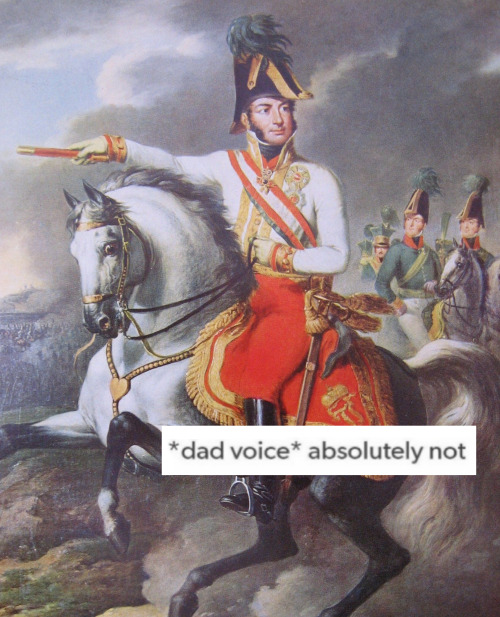

Chuckling Giggling Hehing Cause These Two Separately And Unconnectedly Drawn Pictures Look Like:

chuckling giggling hehing cause these two separately and unconnectedly drawn pictures look like:

"you're just a little hater"

"and?"

put together

-

spaceravioli2 liked this · 1 year ago

spaceravioli2 liked this · 1 year ago -

tr-colorstealer liked this · 2 years ago

tr-colorstealer liked this · 2 years ago -

1ll-def1ned liked this · 2 years ago

1ll-def1ned liked this · 2 years ago -

elderfrogboy liked this · 2 years ago

elderfrogboy liked this · 2 years ago -

kaxen reblogged this · 2 years ago

kaxen reblogged this · 2 years ago -

kaxen liked this · 2 years ago

kaxen liked this · 2 years ago -

cerumilla liked this · 2 years ago

cerumilla liked this · 2 years ago -

v444414j liked this · 2 years ago

v444414j liked this · 2 years ago -

cherrepachka liked this · 2 years ago

cherrepachka liked this · 2 years ago -

pizza-hats-of-the-world-1882 liked this · 2 years ago

pizza-hats-of-the-world-1882 liked this · 2 years ago -

asdeadasasquirrel liked this · 2 years ago

asdeadasasquirrel liked this · 2 years ago -

clove-pinks liked this · 2 years ago

clove-pinks liked this · 2 years ago -

lordansketil reblogged this · 2 years ago

lordansketil reblogged this · 2 years ago -

lordansketil liked this · 2 years ago

lordansketil liked this · 2 years ago -

bringmebacktothe18thcentury liked this · 2 years ago

bringmebacktothe18thcentury liked this · 2 years ago -

empirearchives liked this · 2 years ago

empirearchives liked this · 2 years ago -

gamersix06 liked this · 2 years ago

gamersix06 liked this · 2 years ago -

hesperus-imperator liked this · 2 years ago

hesperus-imperator liked this · 2 years ago -

koda-friedrich reblogged this · 2 years ago

koda-friedrich reblogged this · 2 years ago -

koda-friedrich liked this · 2 years ago

koda-friedrich liked this · 2 years ago -

usergreenpixel liked this · 2 years ago

usergreenpixel liked this · 2 years ago -

count-lero reblogged this · 2 years ago

count-lero reblogged this · 2 years ago -

count-lero liked this · 2 years ago

count-lero liked this · 2 years ago -

acrossthewavesoftime liked this · 2 years ago

acrossthewavesoftime liked this · 2 years ago

More Posts from Count-lero

Part 2 of 3

Archduke Karl of Austria-Teschen and his children, by Johann Ender, 1832. From left to right: Archduke Wilhelm, Archduke Karl Ferdinand, Archduchess Maria Theresa (future Queen of the Two Sicilies), Archduke Karl, Archduke Albrecht, Archduchess Maria Karolina, and Archduke Friedrich Ferdinand. In the left corner there is a bust of Princess Henriette of Naussau-Weilburg, the children's late mother.

Oh my, oh my, what can I say, when it comes to Klemens’ lovely correspondence…

First and foremost, Metternich wrote so much in his lifetime that it’s nearly impossible to estimate the scales of his soaring thought (how far was he carried away in the process - that’s another great question for a lifetime)! As much of his literary heritage has been published, as much is already gone or still hidden from the public eye in the dens of various archives and private collections. Thanks to the efforts of his son, Richard, and other publishers, we can, at least, enjoy a few selections of his private correspondence. However, it was only a tip of an iceberg, for sure. 😅

Since I’m not that interested in Klemens’ perception of Napoleon and his politics, I can’t add much (although you can’t escape this topic, if you start learning about him - Metternich’s whole life was haunted by the presence of the great man ™️ and he couldn’t get rid of it, especially in the 1850s, when to the upcoming generation [or simply more successful politicians of his own age, ehem] he was mostly valuable because of his claims about understanding Napoleon’s “true nature”) …

Perhaps, an acknowledgment of some sort suffices: even though Klemens wasn’t good at foreseeing political trends - the future itself, he definitely possessed an instinct for people. He was a man of his time after all, cultivated, deeply sensitive and receptive, who craved to understand human nature thoroughly both from physiological and psychological points of view. His judgements may seem overly pretentious in some cases but he got to the bottom of things rather well, in my opinion.

In addition, I translated some passages from the Metternich’s biography I love with all my heart, since the author gives a much more comprehensive opinion on the subject there. I do not proclaim those notions as an ultimate truth but I still find his train of thought intriguing. 👀

Intensive personal interactions with Napoleon were for Klemens much more important than official negotiations. Not a single love affair, not a single political event, perhaps, with the exception of the French Revolution, influenced him as much and deeply as these many hours of conversations, often face-to-face, with the most grandiose personality of the era. In Klemens’ dispatches to Franz there are mentions of three- and four-hour-long conversations. He had reason to assert that hardly any of the non-Frenchmen had communicated with Napoleon as long and as directly as he had. "Conversations with him," wrote Metternich later in his portrayal of Napoleon, "have always been full of charm which I find difficult to explain. He outlined the most essential things for him in the subject, discarding unnecessary details, developing his thought clearly and precisely, always finding or coming up with the most appropriate words. These conversations have always been extremely fascinating".

…It is easier to understand Metternich's interest in Napoleon than the French emperor's interest in the Austrian minister. Undoubtedly, Metternich was a brilliant conversationalist – witty, well-informed in politics, with a decent knowledge of natural sciences. But that's not the main point. An explanation can be found in Balzac, who subtly noticed an important trait in Napoleon's character: "Victories over the aristocracy often flattered the emperor's self-esteem no less than the battles won”.

Communication with Metternich, his enticement was for Napoleon one of the forms of self-affirmation in the monarchical-aristocratic world. And it should be noted that he managed to achieve success, although it can be compared with one of his passing victories and not with Austerlitz. The theme "Metternich and Napoleon" is no less interesting psychologically than politically.

Metternich about Napoleon, 1808

An interesting evaluation of the general situation in France, from autumn 1808, given by Austrian ambassador Metternich to his Minister of Foreign Affairs in Vienna, taken from the second volume of “Mémoires, documents et écrits divers”. For context: Metternich had in an earlier missive suggested it might be a good idea to have closer relations with Talleyrand. A suggestion that – hardly surprising – seems to have met with lots of suspicion in Vienna. Metternich tries to prove that, for once, Talleyrand is not to be seen as an enemy to the Austrian cause, that he, to the contrary, tries to stabilize a foreign policy that is about to spiral out of control.

Metternich to Stadion. Paris, 24 September 1808

[…] There are two parties in France, as opposed to each other as the interests of Europe are to the particular ideas of the Emperor.

At the head of one is the Emperor and all the military. The first only wants to extend his influence by means of force, and it is from a degree of nepotism of which there is perhaps no example, a feeling at least as strong in him as egoism; it is, moreover, from the bellicose tendency which a long habit has given to his mind, and from the fiery spirit of his character, to which we owe all the upheavals which, contrary to all reason, and to all sound and settled political calculation, he attempts and unfortunately executes only too much every year.

In short: The guy is unable to discipline himself, and unlike at other courts, there currently is no system in place to keep him in check by other means.

Napoleon sees in France only himself; in Europe and in the whole world, only his family. It is enough to observe him, against all prudence, isolating himself from all the members of his family in order to place them far from him on thrones acquired at the price of so much blood and sacrifice, to see him overthrow weak princes, entirely subject to his will, even to his whims, in order to give these crowns to brothers or relatives over whom he exercises infinitely less influence, - a truth proven daily, to his great chagrin, - not to be able to doubt that his very ambition is subject to his inclination for nepotism.

As interesting and probably correct this assessment by Metternich is (the problems Napoleon had before he took over Portugal and Spain are miniscule compared to those he had after that coup), I could imagine there may be an ulterior motive behind Metternich’s dire warning of nepotism. After all, the Austrian emperor, too, had plenty of brothers, and so had empress Maria Ludovica, most of which were no friends of Metternich.

Personally, I think there may be another motive behind Napoleon’s behaviour than nepotism. As Metternich states himself, Napoleon often struggled to keep his relatives in check. So, when he removed them from Paris and put them on thrones far away, did he do that only in order to do them a favour, or also in order to strengthen his own position in France by removing anyone who might become a figurehead of opposition at home? He removed, one by one:

Eugène (son of the empress, closest thing to a son Napoleon had in the eyes of the public during the Consulate)

Joseph (most respected and most influential of his brothers, according to the constitution his immediate heir)

Louis (father to the boy whom most people saw as Napoleon’s likely future heir)

Jérome (last remaining of his brothers)

Murat (last remaining and highest-ranking family member still in Paris, most respected in the army among all the relatives)

While Lucien of course famously had exiled himself even before the empire. - From what I have read about other courts, it was not unusual to see people flock around other influential figures than the monarch, especially around a possible heir, forming different parties in more or less overt opposition to each other and to certain policies. While it made a court a hotbet for intrigues, it also made it possible for different views and attitudes to coexist there, and to confront the monarch with them. I often feel like Napoleon was keen on removing his relatives from court simply because it removed a source of possible opposition.

Metternich continues:

The military seek only bruises and wounds, especially since he who escapes death is sure of immense rewards.

This must have made for interesting battlefield conversations: Excuse me, sir, before I kill you off, could be so kind as to wound me a little? Nothing too serious, if you please, but with lots of blood. I finally want that damned cross, you know.

There is only one state in France which opens the way to everything, to fortune, to titles, to the constant protection of the Sovereign: it is the military state; one would say that France is populated solely by soldiers and by citizens created to serve it by the sweat of their brow.

The other party is composed of the great mass of the nation, an inert and immovable mass, like the remains of an extinct volcano. At the head of this mass are the most eminent persons of the civil state, and principally M. de Talleyrand, the Minister of Police, and all those who have fortunes to keep, who see no stability in institutions based on ruins, and which, rather than leaning on a durable state of affairs, the anxious genius of the Emperor surrounds only with new ruins.

I’m not sure if Metternich is right in drawing such a clear line between these two parties, to me the distinction seems much more blurry. Plenty of high-ranking officers had married into the circles “who have fortunes to keep”, after all. And there are lots of reports about unrest in the army already from the Polish campaign in 1807. The alleged “Philadelphes” conspiracy is mentioned a lot in German sources for the campaign of 1809, for what those are worth.

This party has existed since 1805; the war of 1806 and 1807 strengthened its means; the bad success of the enterprise against Spain in 1808 made the leaders of the party and their arguments popular; what previous successes had not been able to mitigate had to be strengthened by reverses caused by the most disastrous and immoral of calculations.

This last expression probably refers to the coup in Spain and Napoleon forcing the Bourbons to abdicate so he could put Joseph on the Spanish throne. Which, in my opinion, was not only immoral but mostly clumsy and stupid.

It is in the nature of things that two parties directly opposed can only gain strength at the expense of each other. The reverses in Spain, the destruction of several army corps, the reflux into the interior of troops sustained and fed up to now at the expense of foreigners; the drying up of a host of pecuniary resources, the upheaval given to France by the passage of so many columns which cross it in all directions, all these facts, combined with a hundred other considerations, have weakened the party of universal destruction and strengthened, consequently, the party of interior consolidation, which is only composed of elements equally protective of us.

That’s mostly interesting to me because it alludes to the pecuniary problems Napoleon faced around that very time (or actually always during periods of peace): His army simply was way, WAY too big and a constant drain on France’s finances, even counting the enormous war recompensations the defeated enemies usually had to pay. The Bourbons on returning to France will in the end have to solve that problem that Napoleon merely dragged out as long as he could. But he was very aware of it and tried to find reasons to keep as many troops outside of France as possible, where they had to be provided for and paid by the host country.

I’m not sure if Metternich is necessarily right in everything but he was a diplomat by trade and likely to correctly evaluate his sources. Overall, it’s an interesting assessment of France’s true situation around the time of the congress of Erfurt, and before Napoleon’s Spanish campaign.

L.Mühlbach, Duroc in Berlin

A short scene from a German 19th century author who wrote plenty of (rather lengthy) historical novels: Luise Mühlbach, »Louise of Prussia and her times«. I was astonished to find her works translated into English already, so this is just copied over from gutenberg.org. Duroc learns of the tradition of christmas presents and immediately wants to have one. (The story is reported by Friedrich Gentz to another character in the novel.)

[…] The queen told General Duroc of our German customs, and informed him that this was the day on which the Germans everywhere made presents to each other, and that gifts were laid under Christmas-trees, adorned with burning tapers. At that moment Duroc turned to the king, and said, with his intolerable French amiability: ‚Sire, if this is the day of universal presents in Germany, I believe I will be courageous enough today to ask your majesty for a present in the name of the first consul, General Bonaparte, if your majesty will permit me to do so.’ The king, of course, gave him the desired permission, and Duroc continued: ‘Sire, the present for which I am to ask your majesty, in the name of the first consul, is a bust of your great ancestor, Frederick the Second. The first consul recently examined the statues in the Diana Gallery at the Tuileries; there were the statues of Caesar and Brutus, of Coriolanus and Cicero, of Louis XIV. and Charles V., but the first consul did not see the statue of Frederick the Great, and he deems the collection of the heroes of ancient and modern times incomplete as long as it does not embrace the name of Frederick the Great. Sire, I take the liberty, therefore, to ask you, in the name of France, for a bust of Frederick the Great!’

[Footnote: Historical.]

The request of course endeared Duroc to the Prussian court even more. I like the scene mostly because it shows how different customs were at the time in different regions.

at least tumblr doesn't hate vertical pics